The COVID-AM blog is a partnership between the UMI 3157 iGLOBES and the Institut des Amériques, coordinated by François-Michel Le Tourneau, Deputy Director and Marion Magnan, researcher at the Institute. About the blog.

Drill, Baby, Drill: in Arizona, is Covid-19 being used to push through a mining project?

February 15, 2021

by Anne-Lise Boyer, Research Engineer at the Environment City Society lab (UMR 5600 EVS). Her research focuses on the management of water resources in oasis-cities of Arizona. She holds a PhD in Geography.

by Claude Le Gouill, Associate Researcher at the Centre Recherche et de Documentation des Amériques (CREDA UMR 7227). He works in Bolivia and mining activities in the Andes and Arizona.

Arizona, located in the Southwest part of the United States, is a major copper mining state. Nicknamed the Copper State, it has been the national producer since the start of the 20th century (with over 70% of the production) in a country that is now 4th in the top mining countries of the world. Arizona's subsoil is rich in mineral deposits and has some of the biggest copper mines on the North-American continent, such as the Morenci open mine which produces over 475 000 tons of copper per year. Since the beginning of the 1990s, the mining projects have multiplied in the area, as in other parts of the world. Subjected to long authorization procedures, overseen by the National Environmental Protection Act, the Trump administration and the Covid-19 crisis have recently favored accelerating some mining projects. This is true for the Resolution Copper mine at Oak Flat.

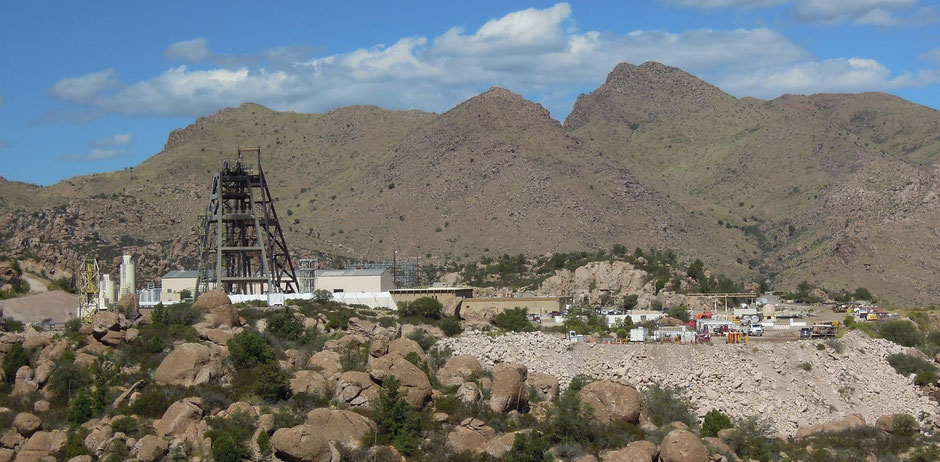

Morenci mine (field photos ALB/CL)

In Pinal County about 60 miles on the east side of Phoenix, Arizona's capital, the old mining district of Magma that was operated from the early 20th century to the mid-1990s by the Magma Copper Company is seeing a regrowth thanks to Resolution Copper's prospecting, a local mining company that belongs to transnationals BHP Billiton (55%) and Rio Tinto (45%). Using Magma mine's abandonned wells to explore the region's deposits since early 2000s, Resolution Copper believes that it could have the largest copper deposit in the world. This mine alone could have the potential to provide 25% of the US' need for copper (Photo).

However, in 2005, while the company was putting together its initial mining plans, local opposition was mounting. Indeed, the region has great value for Phoenix' urban population who goes camping, hiking and climbing there on weekends. It is also dotted with sites considered sacred by the San Carlos Apaches whose reservation is just a few miles from the well. Apache Leap cliff overhangs over the area, so named to commemorate an event from the Indian wars at the end of the 1870s: the Apaches who survived the American calvary's ambush would have retreated to the top of the cliff in order to jump to their death rather than surrender. Yet, according to mine opponents' expert reports, the scope of the mining work proposed by Resolution Copper could destabilize Apache Leap cliff.

This possibility put into question the mining company's discourse on the low environmental impact of its project. It in fact proposes to use the block caving method, the underground version of open pit mining: a large section of rock is undercut, creating an artificial cavern that fills with its own rubble as it collapses. This broken ore falls into a pre-constructed series of funnels and access tunnels underneath the broken ore mass. Though this method has a lesser impact than open pit mining in terms of preservation of the landscape and the storage of waste, it will eventually however cause large sinkholes on the surface which will modify the local geomorphology, with risks to the environment.

In 2014, after a land trade procedure - an exceptional measure that allows public lands to be transferred to the private sector - approved under John McCain's push, former Republican senator of Arizona, and signed by President Obama, Resolution Copper has become the owner of Oak Flat's federal land (2400 acres) which until now belonged to the Tonto National Forest, managed by the U.S. Forest Service. In exchange, the company gave 4500 acres of private tracts of land which were incorporated in the public domain. This exchange created strong opposition from environmental associations (National Audubon Society, Grand Canyon Chapter du Sierra Club), but also from Native American organizations (the San Carlos Apache tribal government gathers there frequently since there are many graves, petroglyphs and sought-after medicinal plants). In 2014, because of the land exchange's exceptional measure, the mine project and the tensions that arose were heavily covered by the media. The pressure from the opponents grew, notibly taken on in Washington by Raul Grijalva, Arizona's Democratic congressman in the House of Representatives. Because of this, Oak Flat was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2016.

For all that, the decision in favor of preserving Oak Flat has not changed much of anything on the plans for the mining project. As is often the case, the development of the mining activity is slowly being put in place and is playing out like a real chess game: each side is moving their pawns forward or backward, controlled by the American environmental legislation, especially the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA). The law, enacted by the American Congress in 1969 in reaction to mounting pressure by environmentalists at the end of the 1960s, forced the decision-makers to take into account the environmental impact of any project likely to change the environment.

This stipulation requires that an environmental impact study be done (Environnemental Impact Statement, EIS) by the agency in charge of confirming the decision, the U.S. National Forest Service for Oak Flat. The expertise work required by EIS started in 2016, causing another rallying movement, with the Oak Flat site being occupied by Apache militants. However, this new protest against the mining project got little media coverage since all eyes were focused on the Dakota Access Pipeline conflict at Standing Rock in North Dakota (mentioned in the article on the Dakotas' Native American situation), where Arizona's activists ended up going. However, finalizing the EIS procedure generates a lot of expert reports and counter-expertise and holding several public meetings, complying with the obligation for the open public comment periods process where the pro-project partisans do everything they can to speed up the procedure while the opponents do all they can to slow it down (obstruction, intermediary lawsuits). So a mining project such as Resolution Copper's can take a dozen years to finalize before the actual mining activities can start.

Today, the Oak Flat mining project is again being discussed. Though the National Forest Service's EIS' final report was not expected until 2021-2022, it was in the end published on January 15, 2021, pressured by a Trump administration favorable toward mining natural resources and hoping to speed up the project before the end of the presidential term.

The document says the Resolution Copper mining project will have limited consequences on the environment, follows current guidelines (specifically the Clean Air Act andClean Water Act) and issued a construction permit on federal lands for the pipeline network and electrical lines associated with the project. This is a crucial step in the mining project's authorization process because EIS' final report sets a sixty day deadline before the land exchange signed in 2014 becomes effective, which makes Resolution Copper full proprietor of Oak Flat, making it possible then for the culmination of the copper mining project.

This decision provoked an outcry. It was seen as a mockery to environmental standards, if not a total affront by the opposing parties. Published during Covid-19, EIS' final report indeed cannot conform to the last step in the participatory process, which is supposed to allow feedback and debates through "comment periods", in accordance with the usual conditions recommended by the law. Indeed, because of the pandemic, the public institutions have closed their offices to visitors, cancelled or delayed public meetings, and moved most procedures virtually (online forms, video conferences for public meetings...).

Several rights groups working on this issue were worried about these Covid-19 related format changes in participation, as well as at a larger scale for local democracy. This was the case for example for the Center For Progressive Reform, joined by 163 other organizations, who had asked the Trump administration in March 2020 to extend all public comment periods, including those related to development projects likely to change the environment. Their petition stated this: "As you are aware, public participation is a central hallmark of the U.S. regulatory system, and the notice and comment process has become the primary vehicle by which the public has been afforded an opportunity to make their views on new rulemakings known to agency decision-makers. (...) The arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, however, threatens to deprive members of the public of this opportunity to meaningfully participate in open rulemakings". This request seems to have gone unheeded.

For Oak Flat, the various parties have 45 days as of January 15, 2021 to voice their objections. However, the Covid-19 context, which is severely hitting the rural Native American populations in Arizona, is strangling the mobilization effort that was so active in the past (Oak Flat occupation, protests in front of Phoenix' Capitol building) for fear of contamination. As stated by congressman R. Grijalva interviewed in The Guardian in November 2020: "The fact they [Trump administration] are doing it during Covid makes it even more disgusting. Trump and Rio Tinto know the tribes’ reaction would be very strong and public under normal circumstances but the tribes are trying to save their people right now.”

The Apache association, Apache Stronghold, that led the opposition to the land exchange and is leading the fight against the Resolution Copper mine project, decided to sue the National Forest Service mid-January on the basis that the mine project is a violation of the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act. This law stipulates that a decision that does not directly concern religious practices can however indirectly weigh on them: "The government cannot substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion". In fact, the USFS' decision to favor the mining project according to them participates in the potential destruction of an Apache sacred site."

So a new legislative battle is starting around a mining project, involving environmental and Native American associations, as is often the case in the Copper State of Arizona. Will the arrival of a Democratic administration be a game-changer?

Anne-Lise Boyer is a researcher at the Environment City Society lab (UMR 5600 EVS). Her PhD is in Geography and her research focuses on the management of water resources in oasis-cities of Arizona.

Claude Le Gouill is an Associate Researcher at the Centre Recherche et de Documentation des Amériques (CREDA UMR 7227). His research is focused on Bolivia and mining activities in the Andes and Arizona.