The COVID-AM blog is a partnership between the UMI 3157 iGLOBES and the Institut des Amériques, coordinated by François-Michel Le Tourneau, Deputy Director and Marion Magnan, researcher at the Institute. About the blog.

Covid-19 among the Wayuu: health protocoles vs fondamental rights

June 26, 2020

by Laura Lema Silva, member of the Scientific committee of the Institut des Amériques and doctoral student in Latin-American studies at the Lumière Lyon University (LCE).

In Colombia, the coronavirus crisis brings to light not only the significant vulnerabilty of the most impoverished populations, the informal workers and the social leaders, but it also reveals the health authorities' lack of understanding of the base of knowledge that has founded the spiritual life of the indigenous communities.

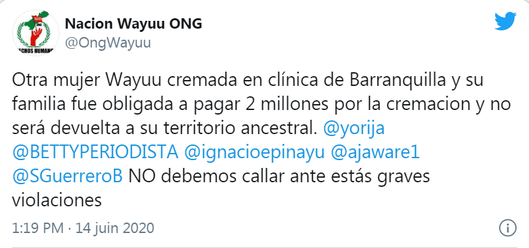

And so, the NGO Nación Wayuu and the anthropologist Weildler Guerra Curvelo, along with several political Wayuu organizations condemned the cremation of several members of the community, between May and June 2020. These cremations pertain to all covid-19 deaths and came to be following the set-up of health protocoles by the Colombian Health Ministry whose goal was to decrease the impact of the virus by reducing the risks tied to the infection. However, they go against the funeral rituals of the Wayuu community.

Among the decried cremations are those of Mauricia Apshana, Luz Delis Pérez Zúñiga and Dublima Morales Machado whose results from the covid-19 test turned out to be negative. Their cremation of their bodies took place without a preliminary consultation with the Wayuu authorities, going against the political autonomy that is granted to them by the Constitution sence 1991. These women could not be buried in the family cemetaries and so the families were unable to do the second buriel rites. Indeed, Weildler Guerra explains: "Los cuerpos muertos entre los wayuu deben ser sometidos a un primer y a un segundo entierro cuyo sentido es suprimido de manera radical al ser destruidos. No se trata de simples ‘usos y costumbres’, entendidos como actos caprichosos y banales basados en la repetición, sino de auténticas ontologías y cosmologías amerindias que regulan las relaciones entre los humanos y entre estos y los agentes inmateriales llamados en el cristianismo ‘almas’ o ‘espíritus’" [1]. With this gesture, Colombia's political and health authorities demonstrated their lack of knowledge of the epistemological significance of the community's funeral rituals. As a matter of fact, they ensure the political stability of the Wayuu by enabling a harmony between the visible and the invisible world.

According to Guerra Curvelo [2], the Wayuu territory situated in the far North of Colombia and Venezuela is crisscrossed with a number of places - generally marked with stones or wells - that symbolize the origin of the thirty clans of the community. They are not just spacial markers, they also signify the introduction of the myth's transhistoric temporality, which is a constant in the daily life of this community. According to Guerra, the myth's time or wayuu sumaiwa is not a time in the past, on the contrary it is a parallel temporality anchored in the present and turned toward the future. It's in the midst of it that transformative events happen from which the land and the people who live in it are shaped. As a matter of fact, the Wayuu's daly world would be the result of the transformation of an original and universal humanity into plants, animals, winds and mountains. These beings all have a moral code and an intentionality, so they have the ontological status of people. Cemetaries have an essential role in this configuration: they determine the territory's distribution between the different clan members and symbolize the place and the moment when individuals cross into the wayuu sumaiwa or invisible world.

The interconnection between daily time and transhistoric time is coupled with a spatial interpenetration between the common visible world and the invisible world, or pülasüü. These intersections give a rythm to the Wayuu's life: crossing from life to death is, as highlighted by Michel Perrin, a time for souls to travel to Jepirra whiere "dead indians" live while waiting for their second burial [3]. In his condemnation of the cremations done recently, Guerra Curvelo contends that once in Jepirra, the "souls" keep their intentionality since they are the ones who ask for a second burial. During the eight years that separate the two funeral rituals, the dead continue to visit, in dreams, the members of their family, adopting their original physical form. The second burial means the departure of the "souls" from Jepirra and their transformation into rain. The rain, Juyá, is a supernatural entity for the Wayuu, that lives in the myth's transhistoric time and the pülasüü world.

So the cremation of the bodies is a violations of the Wayuu's fundamental rights, as well as of the political and territorial autonomy won by the indigenous communities with the enactment of the 1991 Constitution. Indeed, the social-political organization of the community is determined by the constant dialogue with the wayuu sumaiwa. Unable to do the rituals tied to the death of a person means breaking the fragile balance that exists between the visible and the invisible worlds. According to Weildler Guerra, incinerating a person can signify a loss of prestige for their family and interfamily conflicts [4]. And so it's community life, as a whole, that is impacted.

Luz Delys Pérez's cremation led to a protest in the streets of Riochacha, the capital of the La Guajira Department. The women of the deceased's family got together, dressed in red, a color used during the funeral wakes when the death is violent. These women were condemning the symbolic violence of the government and the lack of respect of the Wayuu's fundamental rights.

Faced with this controversy, Interior Minister Alicia Arango qualified these cremations as "serious mistakes" in May. She declared that the government was doing their best so that these burials could be done according to the "customs and traditions" of the indigenous populations, in accordance with the advice given by the World Health Organization. However, on June 14 the NGO Nación Wayuu condemned a new case of automatic cremation à Barranquilla.

This controversy mainly reveals the limits of the Colombian multiculturalism that promotes the culture of indigenous communities while ignoring the systems of belief on which they rest. For all that, it can also be seen as an invitation to explore the social-political organization and spiritual life of the communities in all of their complexities, in so doing given up the notion that these elements are without historical and epistomological foundation.

[1] "The dead bodies of the Wayuu must go through a first and a second burial whose meaning is eliminated in a radical way when they are destroyed. It's not a simple "customs and traditions", thought as capricious and trite based on repetition, but real indigenous ontologies and cosmologies that regulate the relationships of the humans and between humans and the immaterial agents Christianity has called "souls" or "spirits".

[2] GUERRA CURVELO Weildler, Ontología wayuu: categorización, identificación y relaciones de los seres en la sociedad indígena de la península de La Guajira, Colombia, (Thesis in Anthropologu), Universidad de los Andes, 23 de abril de 2019.

[3] PERRIN Michel, Le chemin des Indiens Morts, Paris, Payot, 1976.

[4] To learn more about the resolution of conflicts among the Wayuu, see GUERRA CURVELO Weildler, La disputa y la palabra. La ley en la sociedad wayuu, Bogotá, Ministerio de Cultura, 2002

Laura Lema Silva is a member of the Scientific committee of the Institut des Amériques and doctoral student in Latin-American studies at the Lumière Lyon University (LCE).