The COVID-AM blog is a partnership between the UMI 3157 iGLOBES and the Institut des Amériques, coordinated by François-Michel Le Tourneau, Deputy Director and Marion Magnan, researcher at the Institute. About the blog.

Covid-19 and social inequalities in the americas: autoethnographic analysis of peru

April 26, 2021

by Cristian Terry, Anthropologist, PhD in Social Sciences (University of Lausanne) and a master's in Development studies (Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva)

On February 5, 2020, I took the plane from Milan to Lima. Having finished my work contract in Switzerland, I decided to go see my family and take a vacation in Chile and Bolivia, before continuing my research projects in Peru. On March 16, 2020, one week after I got to Cusco with my family, the Peruvian government declared a national quarantine. The state of emergency, which should have lasted two weeks, was extended for over a year. My initial research projects and overseas conferences went down the tube. However, the public health crisis allowed me to study a totally new topic, of worldwide proportion. Doing a "classic" ethnography was all the more difficult that I was living with my mother and my grandmother, both vulnerable to Covid-19 because of their age. I also did not want to risk getting sick while out in the field and contaminate my family. Furthermore, the Peruvian government was asking the population to stay at home in order to avoid spreading the virus. So I started doing autoethnography[1], combining personal and family experiences[2], in order to study the pandemic and its social impact. This enabled me to continue my work as an anthropologist despite the public health crisis and the lockdown measures. Thanks to the savings I had from my work in Switzerland prior to the pandemic, I was able to stay at home and work remotely while writing articles, following overseas conferences and supervising students via Skype.

The more I advanced in my field work, the more I realized how privileged I was: live in a big house, get housing and food and have access to all the services needed to work comfortably, such as electricity, internet and television (to follow the news and gather some data for my research on the pandemic). Just like the rest of my family, I was able to stay at home, no need for an income, while many Peruvians had to leave their home to work, eat and survive. Indeed, around 70% of the country's population earns its living in the informal sector, without a fixed salary and without health insurance. Furthermore, the "Yo me quedo en casa" (I'm staying home) bonus - government relief money to overcome economic hardship for the poorest - was not enough to cover the expenses of many families. Moreover, many Peruvians said they did not get anything, justifying why they violated the mandatory lockdown (March-June 2020) during the first wave of the pandemic (March-December 2020). The comment "I prefer to die from Covid-19 than from hunger" was made numerous times on television. According to L. Amaya, "51% say they are more afraid of hunger than the coronavirus"[3]. So the poorest populations are the ones that have suffered the most from the pandemic and its socioeconomic and health consequences. Being unable to social distance in the house, in tight quarters, has also caused the spread of the virus at home. Furthermore, how can you avoid spreading the virus if you don't have access to water, essential for frequently washing hands, one of the primary measures to fight against Covid-19?

This situation is at the opposite of what other Peruvians are living, such as my family, who have the means to stay home and put measures in place. During my autoethnographic work in the town of Cusco, I was able to observe the privilege of some families who were easily able to confine themselves, some even doing remote work. For example, we (my family and I) were able to buy large quantities of food in order to avoid leaving the house too often. At the other spectrum, other households, who don't have refrigerators, did their grocery shopping more often. Sometimes, we ordered food delivery instead of cooking. Outings in the city were recreational, as opposed to others who had to leave home in order to eat. In fact, this type of outing (including those that were needed, such as shopping at the grocery store) would enable me to prolong my field observations and witness the evolution of the pandemic at Cusco.

We also allowed ourselves to have family reunions sometimes, for example, a cousin's wedding, even if events that gathered several people were not officially allowed. So some had the luxury to prepare ceremonies, birthdays and trips, as I observed this within my family and my circle in Cusco. For example, one of my cousins celebrated his daughter's first birthday with family and other guests.

In order to pursue my postdoctoral research on tourism and gastronomy, once the mandatory quarantine was over, I took myself to Machu Picchu, just like other middle and upper class Cusconians, as well as national tourists who had the means to travel. Several times I went to the restaurant to study the effects of the pandemic on the number of clients at these establishments. These were "gourmet" restaurants that are not accessible to everybody and that the tourists mainly go to (my postdoctoral research projects prior to the pandemic focused on these types of restaurants and culinary tourism in Cusco). Aside from the pleasure of doing this research, I had an excuse to get fresh air outside of the house. In order to avoid all risk of contamination toward my loved ones, I could easily isolate myself in my room, while for other families who lived in tight spaces, physical distance was difficult to abide by.

Tourists at Machu Picchu, December 2020. The opening of this archeological Inca site followed the reopening of national tourism in the last trimester of 2020. Though tourism brings significant revenue to Cusco, it is also responsible for the spread of the virus in a region that has been severely impacted by the virus (Photo : C. Terry).

I was able to see, through autoethnography, that the pandemic did not impact everybody in the same way. This is not a "democratic virus" that doesn't differentiate between social classes, as the former Peruvian president Vizcarra mentioned, as well as other political personalities. On the contrary, the pandemic actively perpetuates social inequalities not only in Peru, but in the Americas in general[4].

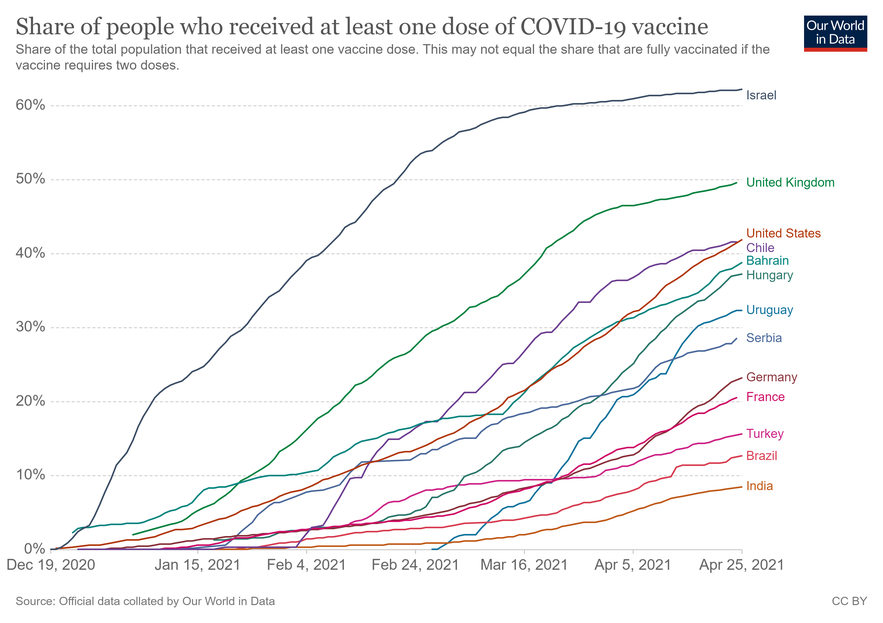

The autoethnography also made me realize that these inequalities are still present today with the distribution of Covid-19 vaccines, this despite the COVAX initiative. My mother who got vaccinated in Chile is a good example. Except for Chile, the rest of Latin America has little access to vaccines for its population and the vaccination process is progressing slowly, in a situation labeled as a "vaccine cacophony". Peru is among the countries who are the most behind the ball, partially because of bad governmental management, the 2020 political crisis and corruption scandals favoring the Chinese vaccine made by Sinopharm which postponed negotiations with other pharmaceutical companies. Since my mother had a residence in Chile, she got vaccinated in February 2021 when Peru had not even started its vaccination campaign (except for the "vacunagate", i.e. the secret vaccination of former president Vizcarra and other personalities from the public, private and medical sectors). Several TV hosts in fact announced that it was possible to get vaccinated in Chile by going on organized tours, for a fee of 1000 dollars (flight, hotel, food and vaccine). Though this information was later refuted, vaccinal tourism not being permitted in Chile, it does however show the privilege of a small fringe of the population who could get vaccinated in another country, whether it be Chile, the United States or Dubai. Just like the presidential candidate's vaccination in the United States, the economist Hernando de Soto, my mother's vaccination shows the financial privilege of some people toward vaccination: money to pay for the trip and the stay. Though my mother's vaccination is a relief for my family and for me with respect to her getting sick, if not dying from Covid-19, it highlights social inequalities, the impact of the pandemic and the means of dealing with it. I also feel part of this group of privileged people because, since I have Suisse citizenship and have a residence in Chile, I could get vaccinated before other Peruvians.

In Peru, with no vaccines, with no government support and with few economic resources, the poorest populations are all the more defenseless in the current situation. If they get seriously sick, how will they pay for oxygen? If there is no room in the public hospital, often overwhelmed, how can they pay for a private clinic?

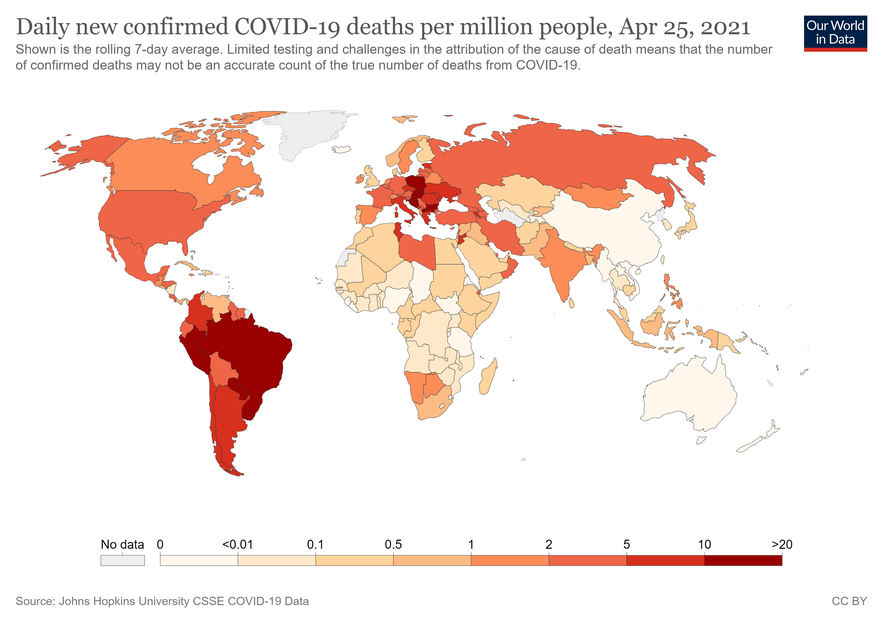

After 200 years of independence and despite an economic growth these past thirty years (increase in GDB without a real distribution of wealth[5]), Peru has maintained significant social inequalities, which explains why some people today (a minority) are more fortunate against the pandemic and can stay home more easily, while others (numerous) really must go out and work. The pandemic is exacerbating social inequalities and these are contributing on their end to the spread of the virus in a country where the new Brazilian variant P.1, a very contagious one, is already spreading among the people. The people who must go out to work in order to live and survive will most likely be more exposed to this variant. There is therefore a real risk of seeing Peru, just like during the first SARS-CoV-2 wave, among the top countries in the world with the highest mortality rate per million people.

Doing an autoethnography during the Covid-19 period has made me more attune to the privilege that me and my family have. The pandemic has certainly upset our lives and our habits. However, we have not had the difficulties that more disadvantaged people have had. Personally, I was able to find the positive side to the pandemic by focusing on the issue as an anthropologist. I also found a way to report these social inequalities from the privileged point of view, to have anthropology be a "professional tool committed to social justice"[6]. In this sense, it is imperative that we think about a new social pact, more equitable and just, separating the link between pandemic and social inequality, briefly laid out here and widely documented by other research in different regions of the planet. This new social pact is necessary to avoid problems tied to Covid-19 (such as the hoarding of vaccines) and other future issues - of the same magnitude or above of the current public health crisis, such as climate change[7] – which seems to strike the most vulnerable populations. Autoethnography can therefore expose social inequalities and transform itself into an auto-critical and empathetic tool before the reality of less privileged people.

[1] See Sikes, P. (2013). Editor’s Introduction : An Autoethnographic Preamble. In P. Sikes (Éd.), Autoethnography: Vol. I (p. xxi‑lii). Los Angeles, etc.: SAGE Publications.

[2] Terry, C. (2020). The "nueva convivencia social” en tiempos de COVID-19. Aproximación desde la auto-etnografía y el caso peruano. Textos y Contextos desde el sur, (Número especial), 101‑128.

[3] Amaya, L. (2020). Cuando el virus no es el único enemigo. In R. H. Asensio (Éd.), Crónicas del gran encierro. Pensando el Perú en tiempos de pandemia (p. 79‑80). Lima.

[4] Bidegain, N., Sabatini, S., & Iwasaki, F. (2020, June). Conversatorio ¿Cómo afecta la pandemia a Latinoamericana? Conférence organisée par la Swiss School of Latin American Studies (SSLAS). Presented in Zurich on June 25, 2020.

[5] Pajuelo, R. (2020). Pandemia y conocimiento : Visibilizando un desafío pendiente en Perú. In R. H. Asensio (Éd.), Crónicas del gran encierro. Pensando el Perú en tiempos de pandemia (p. 178‑184). Lima.

[6] Gerbaudo Suárez, D., Golé, C., & Pérez, C. (2020). Diario etnográfico de tres becarias en cuarentena : Entre el aislamiento y la intimidad colectiva. Perifèria. Revista de Recerca i formació en Antropologia, 25(2), 167‑178.

[7] Cometti, G. (2015). Lorsque le brouillard a cessé de nous écouter. Changement climatique et migration chez les Q’eros des Andes péruviennes. Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, [etc.]: Peter Lang.

Cristian Terry holds a PhD in Social Sciences (University of Lausanne). His research is focused on tourism, gastronomy and textile work in the Andes, especially in the Cusco region. Lately, he's been studying Covid-19 in Peru, having recently published the article "La ‘nueva convivencia social’ en tiempos de Covid-19" and the chapter "'Catch me if you can'. Travel and confinement stories" in the book Échos vides – La poétique du coronavirus (coord. Lya Arthur).