The COVID-AM blog is a partnership between the UMI 3157 iGLOBES and the Institut des Amériques, coordinated by François-Michel Le Tourneau, Deputy Director and Marion Magnan, researcher at the Institute. About the blog.

Cuiabá: after covid, smoke…

September 18, 2020

by Marion Daugeard, doctoral student in geography at the Centre de Recherche et de Documentation sur les Amériques (CREDA - Université Sorbonne Nouvelle) in partnership with the University of Brasília - Center for Sustainable Development (CDS).

After months of lockdown, in suffocating heat that the cuiabanas and cuiabanos are used to unfortunately - although this year had historic records at 108.68ºF on September 10, the city has now been overrun for the past two months by smoke coming from the largest wetland of the world shared by (on the Brazilian side) the States of Mato Grosso (whose capital is Cuiabá) and Mato Grosso do Sul, that is to say the Pantanal. It is currently a victim of fires, in sizeably rare proportions.

As seen in the photos taken in Cuiabá at different times these past few weeks, it's a double crisis - health and environmental - that a portion of Brazil is dealing with (the economic crisis is not far behind...). Leaving the people to believe that they will need to wear a mask - already required since April 13 in town - at home...

COVID-19 IN CUIABÁ

Schools were the first to close, as a precaution on March 13, even though the first official case was not detected until 7 days later. After that, measures were quickly put in place, in particular park closings, controls at store entrances, shorter operating hours, as well as flu vaccination campaigns (Brazil was in full flu season then). Despite their regular disagreements, Cuiabá's mayor and the governor of the State of Mato Grosso favored restrictive measures to avoid a rapid spreading of the virus and provide more time to compensate for the lack of beds in the hospitals, especially in intensive care. With a noticeably small rate of infection until the end of April, we could have thought sometimes that because of the high temperatures of the city of Cuiabá, and more generally of the State of Mato Grosso, right in the dry season then, the climate would have been a barrier to the virus.

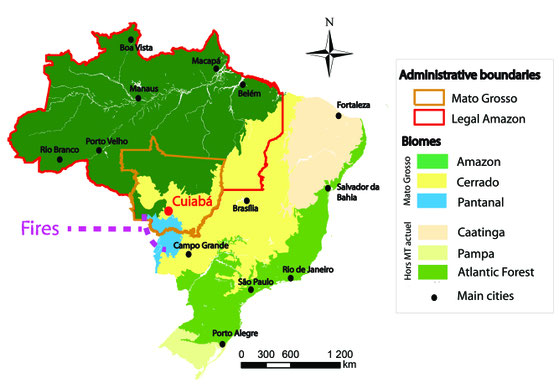

The weak contamination for a time fed these hopes, and pressure increased on the decision-makers to adapt the measures in order to avoid economic problems. While Europe was progressively coming out of the shutdown, local authorities did the same. And yet that is when the State of Mato Grosso, and mainly Cuiabá, saw the number of cases explode. On May 13, 90 % of intensive care unit (UTI) beds were open; end of June, 100 % of the beds were occupied. Returning to a lockdown after a few weeks did not achieve the results hoped for: the number of sick people continued to increase and the number of deaths quadrupled in July. It wasn't until mid-August that the situation improved, probably because cases were identified easier thanks to a "triage" center put in place on the lawn of Cuiabá's stadium and the opening of beds in rural territories. On September 15, the State which has a surface area one and half larger than Michigan and a population of about 3.5 million people (see map below) had 106 895 cases and 3 157 deaths: a rate of close to 900 deaths per million people which would put Mato Grosso - if it was a country - first worldwide in percentage of deaths.

A RETURN TO "NORMAL" UNDER SMOKE

The dry season, that usually starts in the month of May and goes to October, started very early in the region. According to Embrapa Pantanal, the year started with a deficit of 57 % average rainfall. The situation has led to early fires. Fires are not new in the State of Mato Gross: each of its three biomes burn in different proportions each year, but only the Cerrado biome, made up of savanna formations, burns "naturally", especially when it is hit by lightning. The strong anthropogenization of these three biomes, especially in the past 40 years, has not only led to a strong deterioration of the native vegetation, but has also created more frequent fires. Despite ordinances forbidding it, many farmers use slash and burn methods to renew their pastures, practices that are not well controlled, leading to fires. Other burns are meant to "clean" deforested areas or to simply "open" new areas in order to claim them after; yet others are linked to various and diverse incivilities (cigarette butts for example).

Over 16 000 "hot spots[1]" were thus detected in the Pantanal this year by the Institut National de Recherches Spatiales (INPE). The data as of today (September 18), shows that as much as 19 % of the Pantanal might have been consumed by the flames since January, representing over 19 times the surface of the city of São Paulo. Those are the worst numbers observed since records have been taken in the region (1999). A tendency that is likely to continue since the dry season usually goes until October.

Most of the economic activities in the region, namely eco-tourism (already heavily hit by Covid-19) and intensive cattle raising, are also impacted. 62 % of the Encontro das Águas Park, a natural jaguar sanctuary and a popular tourist location, went up in flames. And the capital, Cuiabá, though located at a distance of 62 miles from the fires, is suffocating under the smoke[2].

Though it isn't rare for the city to deal with this type of incident (in fact it isn't the only one to suffer these annoyances since the smoke has gone as far as the State of Paraná as well as the State of Rio Grande do Sul, and has also reached the cities of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo), the length and intensity of the current episode are particularly unusual, and its occurence within a rather tense situation on a health level makes it an exacerbating factor.

HEALTH CRISIS, ENVIRONMENTAL CRISIS: LINKS AND SIMILARITIES

The simultaneous manifestation of these two long crises brings forward the first problem: there are consequences, in different proportions, on the respiratory system. Luckily, the incidence of smoke in the city was noticed at the same time as ITU's started having new beds, and the infection rate was slowing down. Last year, which also saw lots of fires, there were hundreds of smoke-induced hospitalizations and a study by the Fiocruz showed that in 2019 the number of children in the Amazon region hospitalized because of respiratory problems linked to the fires had doubled, leading to an additional cost to the public health system (SUS) of 1.5 million reais. On September 15, a concentration of 738 ppm (parts per million) of carbon monoxide, a highly toxic gas that came from the combustion of the vegetation, was recorded in Cuiabá. Just to give you some idea, the indicative occupational exposure limit values (IOELV) as determined by the European Commission directive in 2017 go from 20 to 100 ppm. The risks of high and prolonged exposure, as is the case in Cuiabá since the end of July, are significant: they go from headaches, nausea and dizziness to more severe cases of respiratory complications, neurological consequences among others.

This year, in Cuiabá, the SUS has already observed a 30 % increase in hospital admissions for respiratory problems, though an increase under what was expected (even if the situation is different from one hospital to another), which can be explained in two ways: some people are avoiding the hospital for fear of catching Covid, and others don't go since some of the respiratory equipment usually used for patients suffering from the intense heat, are being used for Covid patients.

Furthermore, fears are being focused on the indigenous populations, whose mortality rate is one and half times higher than the rest of the population, a situation that could be even worse because of the fires, especially since the NGO Instituto Centro de Vida has noticed that just in the State of Mato Gross (and mainly in the savannas), 758 614 acres of indigenous land have been burnt.

Though the health crisis is exacerbated by the deforestation, deforestation can also trigger epidemics. These dangerous relationships, already revealed with the agricultural colonization of the Amazon (emergence of malaria clusters along the main road infrastructures crossing through the Amazon forest), have been largely documented by the international scientific litterature and been exposed during this global crisis. Though the exact origin of Covid-19 has not been totally established, it seems clear that this is another example of the viral mutation and transmission of animal to human which will happen more often, with deforestation as a contributing factor.

The health and environmental crisis brings us to question our relationship with nature. In that sense, the fact that a city such as Cuiabá, capital of the Brazilian food-processing industry, is confronted with the consequences of both seems quite symbolic. Mato Gross' food-processing industry indeed holds the major portion of the State's lands that have been subdued from the natural formations in the past decades. Though for now the deforestation of the region has not released a virus as serious, in the past few weeks Brazilian scientists have warned of this possibility in the coming years or decades, especially if the deforestation continues.

So, the double crisis and its consequences forces us to think about the world after. But it turns out that the attitude of the Bolsonaro government during the crisis has rather shown a different motivation.

[1] That go from small fires to huge blazes.

[2] Also sometimes exacerbated by fires - though banned - right in the city (gardens, trash cans, abandoned areas, etc.).

Marion Daugeard is a PhD student in geography at the Centre de Recherche et de Documentation sur les Amériques (CREDA - Université Sorbonne Nouvelle) in partnership with the University of Brasília - Center for Sustainable Development (CDS). Read her blog (in French) and find her publications on Researchgate.