The COVID-AM blog is a partnership between the UMI 3157 iGLOBES and the Institut des Amériques, coordinated by François-Michel Le Tourneau, Deputy Director and Marion Magnan, researcher at the Institute. About the blog.

THE pandemic and US-mexico border towns

March 16, 2021

by Cléa Fortuné, doctoral student in American Studies at the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle and member of the Center for Research on the English-speaking World (CREW EA 4399). She's a Teaching Assistant at the Université Grenoble Alpes in the Foreign Language Department (LEA).

US-Mexico border towns, often duplicating urban areas united on each side of the border (Tijuana/San Diego, Mexicali/Calexico, Nogales/Nogales, etc.), are unique in their historic, economic and transborder ties, and this since their creation at the end of the 19th century, beginning of the 20th century.

Despite reinforced controls for the past several decades, border residents cross from one country to the other to visit family and friends, go shopping, participate in events, see the doctor, or even go to school. But, in March 2020, the coronavirus crisis closed the border between the two countries. Unless considered a traveler with a "national interest exemption", it is impossible to cross the border into the United States. Still campaigning for his second presidential term, Donald Trump justified closing the border in the name of national security, and used it to speed up construction of his famous "wall". Not a real wall, it is really various types of barriers that visually separate Mexico from the United States. According to him, these barriers help fight against illegal immigration, but also avoid being "flooded" with Covid-19 cases. All in all, these border closing measures and building new barriers have deeply impacted border towns and their residents.

ENVIRONMENTAL DISASTERS (ALMOST) UNNOTICED BECAUSE OF THE PANDEMIC

In keeping with his promise of building a 450 mile wall before the end of his term in November 2020, the Trump administration sent construction crews in border towns in order to put up new 30 foot high walls, mainly to replace old, smaller ones, that were only guardrails or vehicle barriers.

The majority of the barriers were put in place in Arizona where lands are mainly federal lands, making it easier to set up building sites. While everybody was on lockdown, construction crews actively worked on hundreds of miles of the wall, with a budget of several billion dollars. With the hashtag #CancelTheWall, organizations protested against the use of billions of dollars for an unpopular measure (Pew Hispanic Center's 2019 survey showed that 58% of Americans were opposed to the wall construction, which doesn't mean they don't want less security), and criticized the fact that these expenses could have been allocated to taking care of people with Covid-19. Hundreds of border organizations sent a letter to the federal government demanding an immediate stop to the construction during the pandemic, supported by elected members of Congress, such as Raul Grivalja who condemned the fact that "as the rest of the country shuts down to stop the spread of Covid-19, construction crews continue building Trump’s vanity wall with billions of dollars in stolen funds".

Beyond the controversy on the allocated funds, these same organizations denounced the environmental disasters created by these building sites. They are set up in protected areas, such as the biosphere reserve Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and also at the San Bernardino Wildlife Refuge on the border between Sonora and Arizona. Yet, building a wall in natural habitats leads to important environmental impacts. The barrier thus prevents migrations and with it the survival of wildlife, potentially leading to the extinction of species such as the mountain lion and the javelina on the US side. Furthermore, the wall is being built in desert areas where water is scarce, and the construction officials are pumping groundwater to mix it with the cement used for the foundation of the wall, and to pack the dust that is bothersome during construction, leading to lower water levels and threatening protected species.

The environmental laws should have protected these spaces, but they were circumvented with the use of the Real ID Act, signed under the Bush administration following the September 11 attacks, giving wide use of power to the Department of Homeland Security to bypass any law which could put border security in jeopardy. On top of environmental impacts, there are also economic issues.

ESSENTIAL...."NON ESSENTIAL" TRAVELERS?

Border crossings between Mexico and the United States are significant. US residents cross into Mexico to go visit family and friends, for medical tourism (visits are less expensive in Mexico) and also for leisure activities (movie theaters when there aren't any on the US side, restaurants with a more varied menu, purchase of building material, etc.). As for Mexican border residents who have the documents needed to cross the border, they are a non-negligible source of revenue for small US towns. Just in Arizona, Mexican visitors spent on average 7.3 million dollars per day in restaurants, hotels and stores, shopping being one of the main reasons to cross the border because of the availability of technology products, brand products and products cheaper than in Mexico. In the small border town of Douglas which has 15 000 residents, Mexicans from the sister city Agua Prieta contribute up to 80% of its economy, and a shopping mall was specifically built there for the border Mexicans who come to shop at Walmart, J.C. Penney, and eat in restaurants.

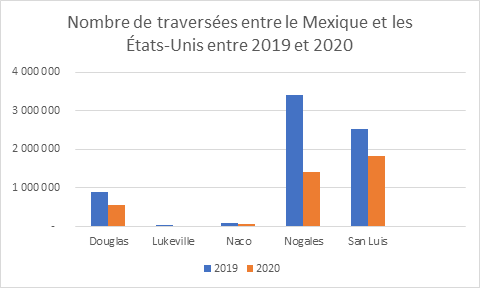

Closing the border to non essential travelers has shaken up these ties: in Nogales, for example, pedestrian crossings have dropped from 3.4 million per year in 2019 to 1.4 million in 2020. The streets of the small American border town streets, having almost become ghost towns, have been deserted and many stores have been forced to close permanently.

Closing the border also means that Americans who do medical tourism are no longer going to American border towns where they used to book rooms (because they found it safer and more comfortable) before going to the doctor in Mexico, which lowered the revenue of American towns.

HUMAN RIGHTS TRAMPLED BY THE PANDEMIC

Though the borders were closed to Mexican consumers during this pandemic, until January 2021 there were also others among the non essential travelers, the asylum seekers. Though international laws forbid the refusal at the border and usually provide the right to not be taken back to the country of origin if there is a chance of persecution or torture, and despite the fact that the UNHCR declared that countries are not allowed to refuse entry or forcibly expulse migrants seeking protection, Donald Trump signed an executive order in April 2020 temporarily suspending immigration. This measure, going against human rights, stopped all asylum seekers, further complicating the migrants situation already blocked in Mexico because of the January 2019 Migrant Protection Protocols. This program, also called Remain in Mexico, required migrants asking for asylum in the United States (estimated at 70 000) to stay in Mexico while waiting for their hearing at the US immigration court. Already persecuted, kidnapped and assassinated by transnational criminal organizations, the migrants in Mexican border towns then became even more vulnerable with the Covid-19 pandemic.

In January 2021, several hours after his presidential inauguration, Joe Biden reopened the borders to asylum seekers and cancelled the Remain in Mexico policy. Finding hope of being able to ask for asylum in the United States, new caravans of Central-American migrants traveled toward the southern border of the US. However, Alejandro Majorkas, the new Secretary of Homeland Security, stated that asylum seekers who wish to enter the United States will have to wait. According to him, "it takes time to rebuild the system from scratch", all the more so when the immigration system has been "gutted" under the Trump administration.

A MULTI-FACETED CRISIS IN BORDER TOWNS

From environmental disasters to economic problems and a disregard for human rights, the Covid-19 pandemic will have particularly hit border towns and its residents. Already significantly impacted by the Trump administration's remarks and measures, they've had to deal with unprecedented measures taken in the name of fighting against the spread of the coronavirus. Despite the new Biden administration's promises to stop building the wall and reform the immigration system, a "return to normal" is not in the horizon.

Cléa Fortuné is a doctoral student in American Studies at the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle and member of the Center for Research on the English-speaking World (CREW EA 4399). Her thesis title was "Border security, local insecurity in the United States/Mexico borderlands. A study of Douglas (Arizona) and Agua Prieta (Sonora)". She is a Teaching Assistant at the Université Grenobles Alpes in the Foreign Language Department (LEA). She is part of the editorial board of the journal RITA (Revue Interdisciplinaire de Travaux sur les Amériques).