The COVID-AM blog is a partnership between the UMI 3157 iGLOBES and the Institut des Amériques, coordinated by François-Michel Le Tourneau, Deputy Director and Marion Magnan, researcher at the Institute. About the blog.

with covid-19, the president drops the jacket. or how trump does not believe in photoGRAPHY (either)

November 2, 2020

by Didier Aubert, Professor in American Studies at the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, member of UMR THALIM, and Fellow at the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion - MAVCOR, Yale University).

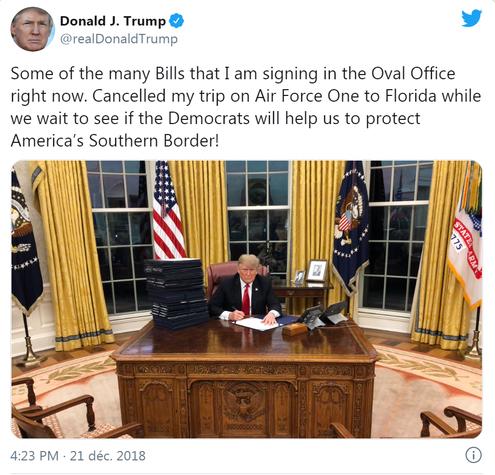

One of the most remarkable images of Donald Trump's campaign will be the one of a president without his jacket looking through documents during his short stay at the Walter Reed military hospital where he had been admitted after testing positive for Covid. In the tidal wave of the American president's incessant televized and "twitterized" comments, this image broadcasted on October 4th by the White House was able to hold the attention of the international press for a few moments, before being submerged, as all other Trump remarks, under the organized saturation of media time-space. This photo however is remarkable for at least three reasons.

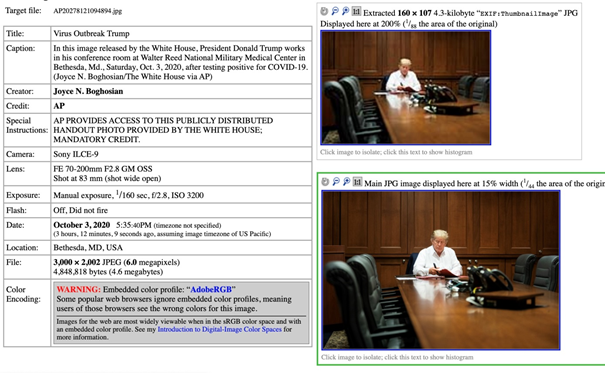

Figures 1 & 2. President Donald J. Trump working in the presidential suite of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland), October 3rd, 2020 after he tested positive for Covid-19 on Thursday, October 1st, 2020 (Photo by Joyce N. Boghosian/White House/AP, source Wikicommons).

1. SIGNING IS PRESIDING

On the basis of this photo, but especially the second shot published at the same time (fig. 2), some commentators thought they could confirm that the documents put before Trump were only blank pages signed by the president. If this is difficult to prove, the hypothesis is enticing because it corresponds to the Trumpian practice of power, in particular his penchant for the ritual of signing in laws, or sometimes executive orders which allow him to impose his political decisions by circumventing Congress, and instantaneously transforming - at least that is how he presents it - his word into action.

Though it's often been repeated that Trump does not read the reports he is given, does not listen much to his advisors, and essentially gets his information from television, he does however behave as if his own words were performing: nuclear disarmement in North Korea, an American economy on the rise, a vaccine for Covid, that's all him. At least that's what he says, and it's perhaps what he believes. The signature of various documents therefore becomes emblematic of a concept of power where the presidential word is personified in an edict. These ceremonies, abondantly photographed, aim to show an image of power in action, with no delays and no intermediaries. It must be remembered that, in the business world, Trump's signature could sometimes be found on bad checks.

2. TRUMP AS CLARK KENT

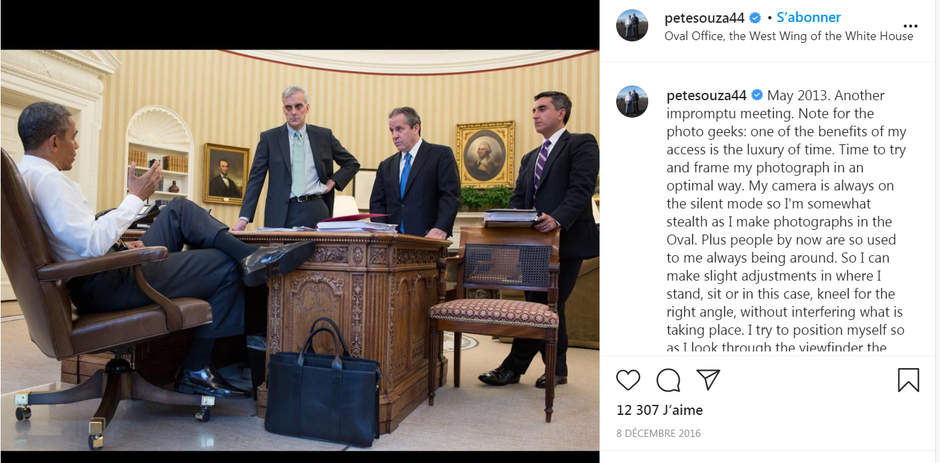

The photo of Trump with just a shirt strangely resonates as an attempt to "Obamize" the presidential figure. Through the eyes of Peter Souza[1], Ronald Reagan and Barack Obama's ex official photographer, Obama had been able to build a public image of relative casual wear and freedom of movement that suggested that the stature of the statesman was adapting to new codes: the modernity of this unique presidency retained a form of gravitas all the more profound in that it also moved in the spheres of empathy and normalcy. Numerous pictures showed Barack Obama having "dropped his jacket" to play with kids, work alone or with his teams, or converse with citizens who came to see him (fig. 4).

This image was also skillfully manufactured, of course. But the official representations of both presidents must make do with two bodies and postures that are diametrically opposed: by the color of the skin, the hair, the silhouette, but also by the clothes. In an official situation (so when he is not playing golf), Donald Trump always or almost always wears a suit, and often a red tie. He does not like to be seen without his jacket, for reasons we can understand. So the incongruity of the October 3rd photo is due to a type of distortion: this Trump both intimate and clothed in the solemness of his responsability reminds us of a visual vocabulary of Obama's presidency. For a few hours, no more, the Republican president presents himself as both studious and humanized by sickness.

A few hours later, pumped with an unprecedented mix of drugs, Donald Trump will in fact put on his cape (his jacket) and will explicitely compare himself to Superman, providing inspiration to the late night TV humorists for the umpteenth time. Filmed getting out of his military helicopter (that has become the visual and sound background of many press meetings), removing his mask from the upper balcony at the White House, Trump quickly got back his iconography of militaristic virility, sometimes magnified by odd slow motions. Where Obama's iconography had been constructed with the use of photography (combining the tradition of photojournalism and the new use of social media), Trump's penchant seems to lean towards Marvel and DC Comics productions.

3. IMAGES AND THE WORLD

Taken by the official White House photographer, the two images of Donald Trump working at Walter Reed pushed a few digital image experts to examine them a little more closely. By looking at the EXIF data (Exchangeable Image File) of the two photos, the journalist Jon Ostrower noticed for example that they had been taken ten minutes apart, visibly in two different locations, with and without a jacket.

The staging of these two images, uncontested by the data, is not really surprising. And we can be skeptical about the political clout of this type of "revelation", for an electoral base that has integrated the "pseudo-events" for a long time as described in the 60s by the American historian Daniel Boorstin as unavoidable in the political debate.

On the other hand, it is rather surprising that the communicators neglected to erase the on-line files' technical data. This very simple operation allows you to publish images without revealing where, when and how they were taken. For the "leader of the free world", you would think it would be an automatic precaution (a lot of equipment, including cell phones, register the GPS coordinates of the location it was taken). Incidently, it would have made it more difficult, in this present case, to see the staging: it is obvious that it is not so much to show the president has been working as it is to offer the media two alternative "visuals" of Trump at work.

At a deeper level, we believe in fact that it is the cultural construction of digital technology that has come to make us even forget the idea of anchoring an image in the world. Photography is less a vertu of proof (the confirmed proof of the "real trace" that the photographic image is) than its ease of publication and instant proliferation. In a recent book, André Rouillé wrote that "the fluidity of digital images, the flexibility of their form and the volatility of their relationship to objects are the reverse side of the immobility of printed film, of their rigidity and their adherence to objects."[2]. More so than the continued ambiguity of the image content, the EXIF data can actually be seen as a contemporary version of the photographic trace, of the "adherence to objects" long considered as a specificity of the medium: they are likely to prove the anchoring of an image in a location and at a specific moment. That they were not erased by a communication team briefly tempted to construct a "new image" of the president could be due to forgetfulness or incompetence. We can surely see this as a sign (one more) of a serious disinterest from this administration in connections between word, image and the world.

[1] Pete Souza's Instagram account, his works, his public interventions have consistently shown these contrasts. See for example the documentary focused on how he works, called The Way I See It, and broadcasted on the progressive channel MSNBC.

[2] André Rouillé, La photo numérique, une force néolibérale, Paris, L’échappée, p. 69.

Didier Aubert is a Professor in American Studies at the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, member of UMR THALIM, and Fellow at the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion - MAVCOR, Yale University).